Unlocking True Randomness. Quantum Computers for Entropy

Last week, I had the chance to attend a one-day course on quantum computing at SCAYLE. While it was just a high-level introduction, it gave me a solid intuition about the fascinating world of quantum mechanics and computing.

In this post, I’ll take things a step further by using a real quantum computer as a source of entropy to generate truly random numbers. With these numbers, I’ll create a private key on the Ethereum blockchain and deposit some funds into the associated address.

⚠️ Disclaimer: This is purely experimental. Randomness for private key generation is important but also has to be private. With this example you have no guarantees of such thing.

Introduction to Quantum Computing

First and foremost, while quantum computing has made incredible progress, we’re still in the early stages. Today’s quantum computers boast a growing number of qubits, but the real challenge lies in maintaining coherence. Meaning, keeping noise under control. That’s referred to as the NISQ era (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum).

We can already do some basic computations with quantum computers, like factorise a number in its primes (eg 21 in 7*3) but we are still far from factorising huge numbers like the ones that will break the elliptic curve cryptography.

The basic principle behind is not very intuitive but simple. Quantum computing leverages the principles of quantum mechanics to process information:

- 💻 Classical computing. Bits can take two values

0and1. - 🌀 Quantum computing. Qubits can be both

0or1with some probability.

I think of it as a coin being flipped flying in the air. Its state is neither 0 nor 1. It can be both. But you won’t know until the coin hits the ground. In the case of an unbiased coin both probabilities are the same.

One of the coolest things about quantum computing is that it allows to explore options faster. For example, Shor’s algorithm allows factorising numbers into primes way faster than with classic computers. The fact that a qubit can be in both states benefits that. The intuition behind this can be seen here, searching for the exit in a maze.

Without going deep into the math, let’s see the basics. This fancy expression just means that a qubit can be both a 0 or 1 with some probability.

- The indicates the probability of the qubit collapsing to a

0. - And the probability of it collapsing to a

1.

This rule has to hold true. Which basically means that if there is a 30% change of a 0 there has to be 70% chance of a 1. Both probabilities 30%+70% have to add up to 100%.

A qubit that has the same probability of 0 and 1 can be expressed as follows. That’s a 50/50% change of each. Think of the flipping a coin example.

In reality each probability is a complex number, with a real and imaginary part. But well, for the example we only care about the module.

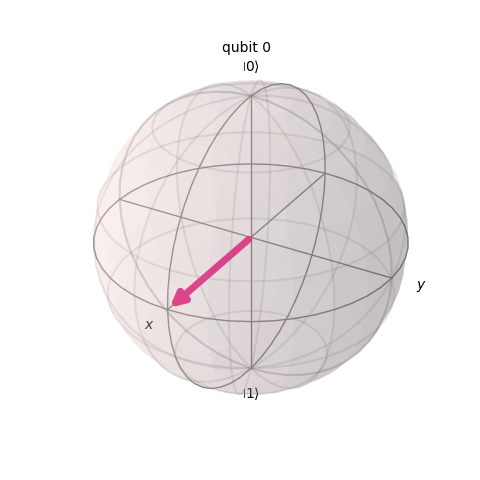

Thanks to qiskit we can plot the state vector of a qubit in superposition in the Bloch sphere as follows.

1from qiskit.quantum_info import Statevector

2from math import sqrt

3import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

4

5x = Statevector([1/sqrt(2), 1/sqrt(2)])

6x.draw('bloch')

7plt.show()

Oversimplifying, the qubit is just a vector pointing up or down. If it points up, it will always collapse to a 0. But it can point anywhere and that will set the probabilities.

Quantum Simulators

Unfortunately, quantum computers are not yet commodity hardware that anyone can have at home. They are rather big and must stay at a very low temperature near absolute zero.

Luckily the Python library qiskit allows us to simulate the behaviour of a quantum computer in your laptop. This allows you to test and prototype before sending the code to a real quantum computer.

Let’s define a simple circuit using quantum logical gates. These gates are conceptually similar to the classic logic gates such as AND, OR and NOT. They just transform the input according to some rules.

Our example is rather simple. We apply the Hadamard gate to all qubits. This sets the probability of the qubit collapsing to 0 or 1 to 50:50. Then we measure it. This is a simple random number generator. We use 256 qubits and measure them once. This gives us a random number with 256 bits.

1from qiskit import QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister, QuantumCircuit

2from qiskit_aer import AerSimulator

3

4q = QuantumRegister(256)

5c = ClassicalRegister(256)

6circ = QuantumCircuit(q, c)

7circ.h(q)

8circ.measure(q, c)

9

10backend = AerSimulator()

11job = backend.run(circ, shots=1, memory=True)

12print(job.result().get_memory())

The example is interesting but this is just a simulated environment. Nothing is real. The randomness we get here would be like the one of the random package. A pseudo-randomness.

Let’s see how to get randomness from a real quantum computer for your key generation.

Using a Real Quantum Computer

Thanks to IBM Quantum we can run our previous code in a real quantum computer. IBM offers some kind of Quantum as a Service. Their quantum computer sits behind an API and they allow some free usage, 10 minutes a month. That’s enough for our program. Go to their website, register and get your API key. Replace token value.

We have to tweak a bit the code since none of their computers have 256 qubits. Instead we use 64 qubits and measure 4 times. That’s equivalent and gives us a random number with 256 bits.

Collapse Code Expand Code

1from qiskit import QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister, QuantumCircuit

2from qiskit import transpile

3from qiskit_ibm_runtime import QiskitRuntimeService

4from eth_keys import keys

5

6q = QuantumRegister(64)

7c = ClassicalRegister(64)

8circ = QuantumCircuit(q, c)

9circ.h(q)

10circ.measure(q, c)

11

12service = QiskitRuntimeService(channel="ibm_quantum", token="YOUR_TOKEN")

13backend = service.backend('ibm_kyiv')

14qc_basis = transpile(circ, backend)

15job = backend.run(qc_basis, shots=4)

16

17counts = job.result().to_dict()["results"][0]["data"]["counts"]

18priv_key = ''.join(counts.keys()).replace('0x', '')

19

20private_key_bytes = bytes.fromhex(priv_key)

21private_key_obj = keys.PrivateKey(private_key_bytes)

22

23public_key = private_key_obj.public_key

24public_key_hex = public_key.to_bytes().hex()

25

26eth_address = public_key.to_checksum_address()

27

28print(f"Private Key: {priv_key}")

29print(f"Ethereum Address: {eth_address}")

Let’s explain what the code does:

- Uses 64 qubits in superposition state. Same chance of it collapsing to a

0or1. That’s what thehor Hadamard gate does. - Transpiles our code since unfortunately, the target computer doesn’t support the Hadamard gate.

- Runs the simulation 4 times. We get 64 random bits in each run.

- We join all 64 bits into a random number of 256 bits.

- We use that random number as a private key for the Ethereum blockchain.

Quite cool, right? Your code has been transmitted over the Internet to the IBM quantum computer. A set of qubits has been configured according to your circuit, and measurements have been taken of these qubits, which are maintained at temperatures near absolute zero (approximately 0.015 Kelvin or -273°C).

Just for fun, here is the Ethereum account that we have generated. Its funded with 30€ so if you can take it, all yours.

Of course, don’t use this method to generate entropy for your private keys. While the randomness can be okay, you don’t know if anyone has knowledge of it. Maybe IBM is storing logs with the results.